Dr. Hartmut Schorrig, www.vishia.org, 2020-11-13

See also

1. Approach

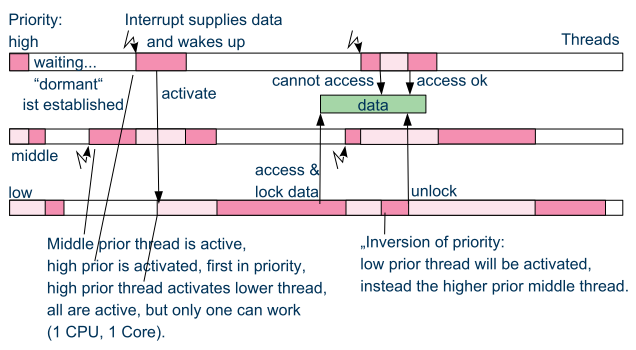

In Real Time Operation Systems (RTOS) usual an mutual excluded data access is done with using mechanism of data locking available in the thread scheduler of the RTOS (semaphores, monitor etc. ). It looks like:

This example shows additionally the problematic of inversion of priority, which should be regarded by the RTOS. The disadvantages are:

-

The lock and unlock needs some calculation time: The Scheduler should be informed. It notices the lock in a special table. It is a system call of a RTOS routine.

-

The locking mechanism cannot be used if one of the 'threads' is really an interrupt routine. Only real operation system threads can use this approach.

The other possibility of mutual exclusion of data access is the atomic access approach using 'compare and swap'. It is possible to use both in interrupts and in multithreading.

'compare and swap' can only be used if only one cell in RAM is the candidate of mutex. This is an important restriction, but some algorithm especially for container handling are possible with well-thouht-out usage of dedicate variables for mutex with 'compare and swap'.

'compare and swap' is used for example in Java container in the java.util.concurrent package. It was introduced with Java-5 in about 2004. The Java approach was: minimize the calculation time, because Java is often use in server applications which has to do a lot of requests. The sum of calculation time is the point of interest.

2. Basics

2.1. The compare and swap basic instruction

The basic of 'compare and swap' is a machine instruction which was introduced already with the Intel 486 processor family:

lock cmpxchg addr, expect

See https://software.intel.com/content/www/us/en/develop/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-1-2a-2b-2c-2d-3a-3b-3c-3d-and-4.html, then in the downloaded pdf page Vol.2A 3/189 or search the instruction CMPXCHG.

addr is a given memory address. expect is a CPU-register which contains the expected value. The update value is contained in the AL or AX register (accumulator). The instruction can perform for 8, 16, 32 or 64 bit access to the memory.

An important feature of this instruction is: It accesses the real memory (RAM) through the caching. This is essential in multicore systems.

For other processors using cache and/or multicore adequate machine instructions are existing. Because the 'compare and swap' istruction is processor specific, it should be organized in a special OSAL or HAL adaption layer ('Operation System Adaption Layer' or 'Hardware Adaption Layer'. Hence for Microsoft’s Windows there is an 'Application Interface' (API) routine named InterlockedCompareExchange… which invokes this instruction on an Intel bases system.

For simple processors often used in embedded control such an instruction is not existent. But the functionality is the same as (for example for Texas Instruments TMS320C28 series):

int32 compareAndSwap_AtomicInt32(int32 volatile* reference, int32 expect, int32 update) {

__asm(" setc INTM");

int32 read = *reference;

if(read == expect) {

*reference = update;

}

__asm(" clrc INTM");

return read;

}

It is implemented in C language (or C++) but with special assembler instructions: The important thing is the interrupt disabling and enabling. It means the approach B) is used (chapter above), but not in the users algorithm, instead in a 'system routine' or OSAL or HAL layer. The application source uses only the common present `compareAndSwap_AtomicInt… ` invocation which is adapted for gcc on Intel-based PC, for Windows etc. in form:

int32 compareAndSwap_AtomicInt32(int32 volatile* reference, int32 expect, int32 update) {

return InterlockedCompareExchange((uint32*)reference, (uint32)update, (uint32)expect);

}

and for GCC for Intel based execution:

int32 compareAndSwap_AtomicInt32(int32 volatile* reference, int32 expect, int32 update)

{ __typeof (*reference) ret;

__asm __volatile ( "lock cmpxchgl %2, %1"

: "=a" (ret), "=m" (*reference)

: "r" (update), "m" (*reference), "0" (expect));

return ret;

}

All three routines have the same signature, it are equal for usage in the application. The implementations are different due to the platform.

2.2. The basic idea: Repeat the access

The basic idea of atomic access with compare and swap is the repeated calculation of the new content in memory if the access fails. It is shown by an add instruction:

extern volatile int sum; sum += val;

This is the non-mutual excluded variant: The += operation is not a simple operation. It reads, adds and writes in some machine instruction. During read and add, before write, the content of sum may be changed by another thread or interrupt, and the result of the last written content wins, the result is faulty regarding all threads.

Hence the access read, add and write should be divided in its parts. Writing should only be done if the content has been unchanged in comparison to the used base value for addition. It this is not true, the whole calculation have to be repeated:

/**Simple add a value to a given variable. */

static inline void addInt_Atomic_emC(int volatile* addr, int val) {

int ctAbort = 1000;

int valueLast = *addr;

int valueExpect;

do {

valueExpect = valueLast;

int valueNew = valueLast + val;

valueLast = compareAndSwap_AtomicInt(addr, valueExpect, valueNew);

} while( valueLast != valueExpect && --ctAbort >=0);

ASSERT_emC(ctAbort >=0, "addInt_Atomic_emC faulty", (int)(intPTR)addr, val);

}

This is the complete add operation using the atomic access like programmed in emC/Base/Atomic_emC.h for C/++ usage:

The fundamental and longest instruction is the compareAndSwap itself. It accesses through the cache, hence it is a longer operation if caching is active. The important thing is, that the valueLast does not need an extra access to the memory, it is given as result of the CMPXCHG instruction itself, loading in the accumulator register. Hence the operation is named "compareAndSwap" and not "…Set" which was more evident for the isolated instruction itself. The result value as old value is necessary for the next loop if the write access fails. The read access is already done during the compare part of the instruction from memory through the cache. Only the first access needs an extra access to the memory, maybe not through the cache (depending on the compilers machine code generation) with the volatile modifier. But because the compareAndSwap.. accesses through the cache, it is proper checked.

The addition is always executed with the given valueLast which is the valueExpect for the CMPXCHG instruction. That is correct. It should be repeated with the given valueLast in the next while-loop if the access failes.

Fails the access? Usually this is not the case. It means: The whole operation is fast, only one time it is written to the RAM. The only longer operation is the access through the cache, but that is necessary and wanted.

The access fails if another thread changes the content on the memory between the read access and the subsequent write. The probability of changing the memory by another thread depends on the possible thread execution cycle time and the less time difference between read and write of this access. For example if the time difference is 100 ns (a few instructions) and the cycle of the other thread is 1 ms, the probability is 1 : 10000. If the lower thread (which is interrupted with a cycle of 1 ms) runs in a cycle of 10 ms, it occurrs one time in 100 seconds. It is often for a long running system. Only in a cycle of 100 seconds the lower prior thread needs additional about 20..100 ns for a second memory access and calculation. This is effective.

The possibility that the second access is also interrupted is 0 if only one possible interrupting thread exists. It is rarely if a third thread interrupts exactly the second access. Hence a while loop is need because for the rarely case of a second or third … interrupting.

The ctAbort may be seen as unnecessary. But any while loop should be terminate by such an abort count, it is a principle. If the memory is defect, it is possible that the while loop runs infinite. Then the ctAbort helps. It is a less-effort additional instruction which may be important in an improbable situation, but which can occur, think about "murphy’s law". The ASSERT_emC(…) can be empty, it does not need calculation time for a tested target system.

2.3. Disable interrupt or compareAndSwap to perform atomic access

General the disabling of all or dedicated interrupts is another solution for the atomic access. It disables also thread switches in a RTOS scheduler. Hence it is a real alternative.

The adding problem of the chapter before can very more simple solved with:

extern volatile int sum; disable_interrupt(); sum += val; enable_interrupt();

If all interrupts are disabled, the sum might not be changed while reading, adding and saving. This is true for a simple embedded system. It is not true if the hardware may change the sum too, for example if it is a read- und writeable register in an FPGA, which will be changed sometimes by the FPGA logik. Of course, the FPGA functionality should be disabled too in this case, it is a special problem. Apart from that, the disabling of interrupts is a widerspread approach for embedded control software.

The problem for disabling interrupt is: It is possible for simple embedded platforms, but not approachable if a execution security protected level is given for the CPU, especially on systems where an operation system is present.

Why is disabling interrupt forbidden for application software in non protected level ? Because: A forgotten enabling or a too long disable time can disturb the whole system. A small stupid programming error should not crash the system, that is the principle.

The second reason for the CMPXCHG instruction and the 'compare and swap' technology is: It helps if caching is used. The CMPXCHG accesses through the cache to the real memory, it is necessary for multi core systems.

Now, it is worth considering whether the following approach should be done:

-

A) Using 'compare and swap' only for RTOS driven systems, using disabling interrupt for cheap poor hardware.

-

B) Using 'compare and swap' anytime independent of the hardware. The core compare and swap operation is put into effect for poor hardware with disabling interrupt, but only in the implementation of the 'compare and swap' operation. Disabling interrupt is never used in application sources.

The approach B) has the advantage, that the algorithm are independent of the target implementation system. Especially an application can be tested on another, high performing platform maybe with test environments. Hence this approach should be favored.

The approach A) has some less calculation times in special cases. It means it should be possible to uses for special cases with fast realtime requirements. For tests on an system without disabling interrupt possibility the disable_interrupt() routine should be an empty operation, and the test environment does not really require disabling interrupt for an test approach.

The question is: How many more calculation time is necessary in comparison of both technologies. This is discussed in chapter TODO

3. A ring buffer implementation with compareAndSwap

A ring buffer, circular buffer, is a common approach to store data in some threads, or interrupts, and read out in a special processing thread. Especially an event queue, often used for state machines, for processing several task etc. can based on a ring buffer.

The simple case, write in one thread or interrupt, read in another thread, does not need any mutex.

3.1. Basic implementation of a RingBuffer

It is implemented in emC/Base/RingBuffer_emC.*

The data itself should be stored in a simple array with the determined type of the ring buffer elements and the given size:

#define SIZE_MYRingBuffer 123 MyElementType myDataRingBuffer[SIZE_MYRingBuffer];

Of course allocation of the ring buffer array is possible and may be recommended:

void myInitRoutine(int sizeRingbuffer) {

MyElementType* myDataRingbuffer =

(MyElementType*)(malloc(sizeRingbuffer * sizeof(MyElementType));

The management of the read- and write pointer is centralized in a

typedef struct RingBuffer_emC_T {

uint nrofEntries; //it stores nrofEntries

int ctModify;

uint ixRd; //use signed because difference building.

uint ixWr; //+rd and wr-pointer

} RingBuffer_emC_s;

To write into the ring buffer without mutex only the following is necessary:

int ixWrNext = myRingBuffer->ixWr +1;

if(ixWrNext >= myRingBuffer->nrofEntries) {

ixWrNext = 0; //to wrap

}

if(ixWrNext != myRingBuffer->ixRd) {

myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixWr] = dataToStrore;

myRingBuffer->ixWr = ixWrNext;

}

It is simple and effective. The few operations do not need long computing time. It can be performed in a fast interrupt.

The ring buffer is fullfilled if a ixWrNext would hit the ixRd. Then it is not able to detect whether the buffer is empty or full filled. Hence the ixWr stops one point before ixRd. Both indices are wrapping on the end, it is a fast operation. A little bit more faster is: Usage of a power-2 size and OR the ixWr with a mask. But that is a special solution.

If the ring buffer is full filled, a writing is skipped. Any error message or such can be performed in an else branch, but usual the read access should be performed too. The state of the ring buffer is obviously for example while debugging, or by an additional check algorithm, by monitoring the ixRd and ixWr.

The basic read access is also simple:

if(myRingBuffer->ixRd != myRingBuffer->ixWr) {

dataToRead = myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixRd];

//...process the data

int ixRdNext = myRingBuffer->ixRd +1;

if(ixRdNext >= myRingBuffer->nrofEntries) {

ixRdNext = 0; //to wrap

}

myRingBuffer->ixRd = ixRdNext;

}

3.2. Problems with more as one writing thread or interrupt

If disabling interrupt is used, the whole writing process can be wrapped with

disable_interrupt();

int ixWrNext = myRingBuffer->ixWr +1;

if(ixWrNext >= myRingBuffer->nrofEntries) {

ixWrNext = 0; //to wrap

}

if(ixWrNext != myRingBuffer->ixRd) {

myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixWr] = dataToStrore;

myRingBuffer->ixWr = ixWrNext;

}

enable_interrupt();

If the algorithm gets an else branch, the enable_interrupt should be performed in the if branch after …→ixWr = ixWrNext but also as first instruction of the else branch, which may have a longer calculation time. The sum of disable time is not too great, but also not minimalistic. A fast interrupt can be delayed though it won’t use the ring buffer. The problem may be the dataToStore-copy time.

It may be better to enable the interrupt before writing the data.

disable_interrupt();

int ixWrNext = myRingBuffer->ixWr +1;

if(ixWrNext >= myRingBuffer->nrofEntries) {

ixWrNext = 0; //to wrap

}

if(ixWrNext != myRingBuffer->ixRd) {

int ixWrUsed = myRingBuffer->ixWr;

myRingBuffer->ixWr = ixWrNext;

enable_interrupt();

//...

myDataRingBuffer[ixWrUsed] = dataToStore;

} else

enable_interrupt();

//maybe produce a log message buffer full

}

It has a constant time for disabling interrupt independent of the writing process. But yet a read can be performed with incomplete written data with the read access above, because the ixWr is incremented and stored already before the write data is complete. To prevent this situation on reading it should be tested evaluating the data whether they are complete. The read should be divide in two parts:

if(myRingBuffer->ixRd != myRingBuffer->ixWr) {

dataToRead = myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixRd];

if(isComplete_MyDataToRead(dataToRead) {

//...process the data

myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixRd] = incomplete_designation;

//after access all data from ring buffer increment ixRd,

//because only now new data can be written:

int ixRdNext = myRingBuffer->ixRd +1;

if(ixRdNext >= myRingBuffer->nrofEntries) {

ixRdNext = 0; //to wrap

}

myRingBuffer->ixRd = ixRdNext;

}

}

The kind how the data consistent is detected should be defined application-specific. For example if references (pointer) are stored, a null pointer is incomplete, a valid pointer is complete. Or if float values are expected, a special INFINITY value can be used to designate a not written write position. But hence on reading the position should be set back to the incomplete value, which is performed in the incomplete_designation line which should be programmed in the user’s algorithm too.

If the element data of the ring buffer consists of more as one part, the special designating part of complete data should be written as last. Then the consistence is given if this last part is written.

3.3. Using inline subroutines for managing the ring buffer

The last examples in the chapter above suggest using a subroutine for the statements to handle the indices in the RingBuffer_emC data structure.

int ixWr = add_RingBuffer_emC(myRingBuffer);

if(ixWr >=0) {

//...

myDataRingBuffer[ixWr] = dataToStore;

}

The read is divide in two accesses:

int ixRd = next_RingBuffer_emC(myRingBuffer);

if(ixRd >=0) {

//first check whether complete new data are given:

if( myDataRingBuffer[ixRd].xyz == valid) {

dataToRead = myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixRd];

myDataRingBuffer[myRingBuffer->ixRd].xyz = incomplete_designation;

quitNext_RingBuffer_emC(myRingBuffer, ixRd)

}

}

The code in the application level will be more simple. Now inside the subroutines it can be determined whether interrupt disabling is used or a compare and swap approach. It does not depend on the application algorithm, it does only depend on the properties of the target system.

3.4. Using cmpAndSwap

TODO it is implemented but not documented. 2021-01-06